Patient Guidebook

The Gastrectomy Patient Guidebook is available below for your viewing.

Below, there are some additional resources which outline what occurs during a gastrectomy.

The Gastrectomy Patient Guidebook is available below for your viewing.

Below, there are some additional resources which outline what occurs during a gastrectomy.

The gastrointestinal system is one long tube from the mouth down. After we ingest food, it is continuously broken down and digested through different chemical and physical processes. The accessory organs of the gastrointestinal system include the tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver and gallbladder. Here is a brief outline of the digestive process:

Figure 1: The Gastrointestinal System1

If a gastric cancer diagnosis is made early enough, the disease is more likely to be considered curable. This assessment is made based on the stage of the tumor using the TNM system. Surgery for early gastric cancer tries to cure the disease by cutting out the organs affected by cancer cells. There are several different surgical options available to patients and their doctors. Some of the major ones are explained below.

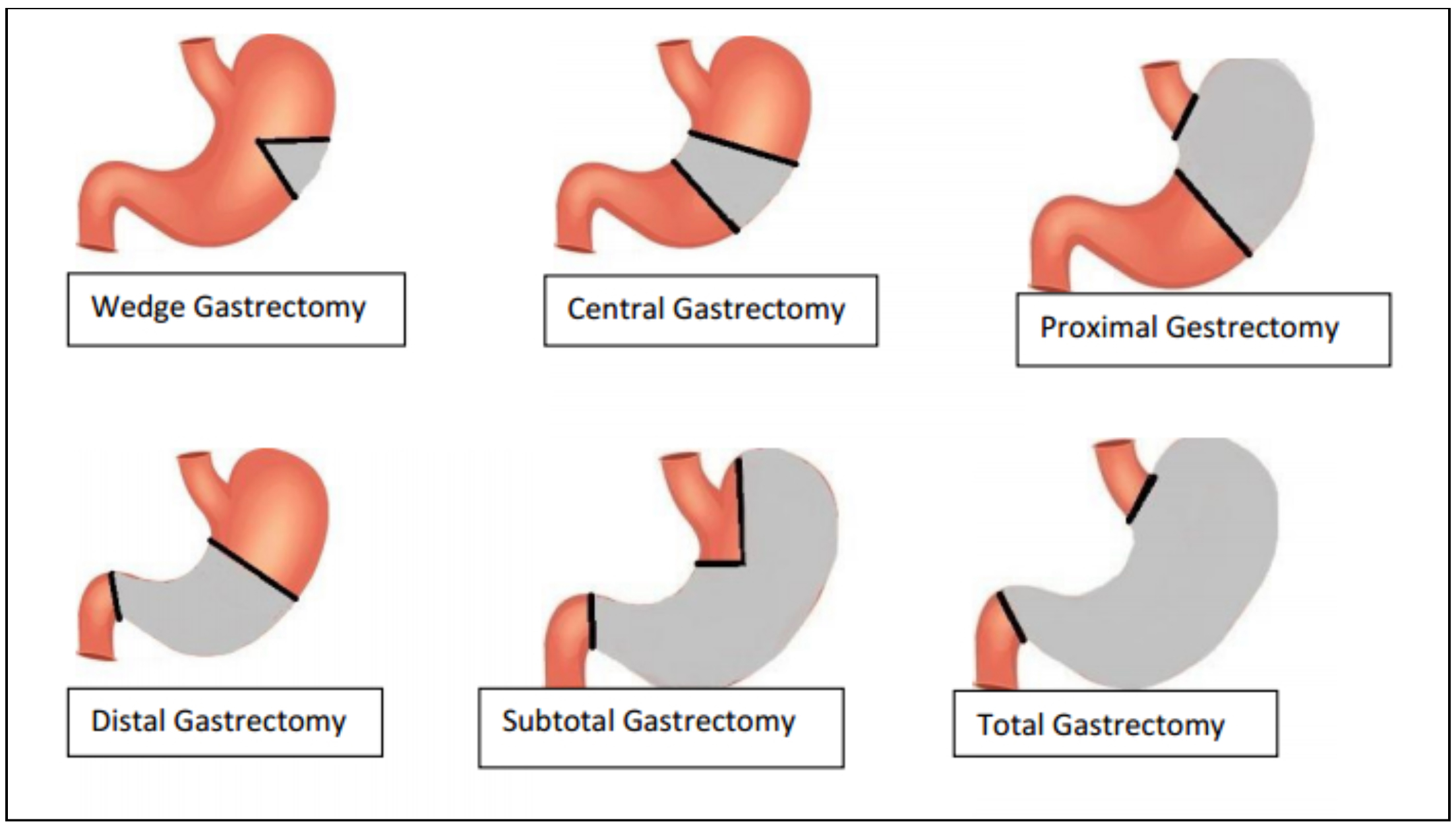

“Gastrectomy” means to “cut out the stomach”. There are different types of gastrectomy procedures which can be selected based on the location and the extent of a patient’s tumor. Please see Figure 12.

Figure 2: Showing the different regions of the stomach which may be cut out during a gastrectomy surgery; the grey area represents the removed part of the stomach3

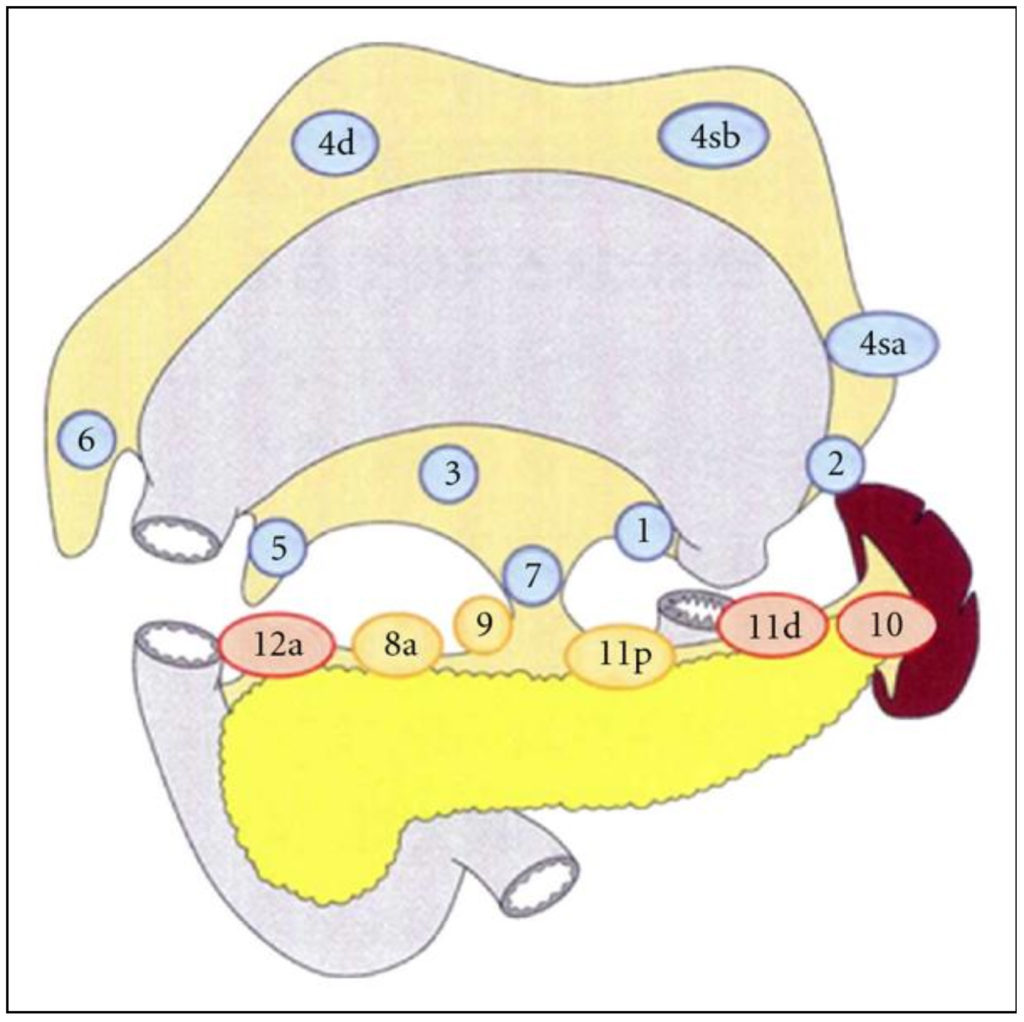

“Lymphadenectomy” means to “cut out the lymph nodes”. It is also known as a “lymph node dissection”. This is almost always done with a gastrectomy because lymph nodes are a common secondary site for cancer and they provide an easy route for it to spread through the body. In this surgery, lymph nodes are cut out and inspected for the presence of cancer cells.

One of the biggest ongoing debates in gastric cancer treatment amongst experts is what type of lymphadenectomy should be done. See Figure 21

It is important to understand that higher numbers correspond to more nodes being removed. For example, a D2 resection removes all the same nodal groups as a D1+ does, plus a few more! Thus, D2 is a more extensive procedure than D1+ is.

Figure 3: This shows the locations of lymph node groups that are commonly removed in D1 (blue), D1+ (yellow) and D2 (red) lymphadenectomies accompanying a total gastrectomy2.

Currently in North America, doctors tend to use the D1 or D1+ technique most often. On the other hand, surgeons in East Asian countries usually use the D2 approach as standard of treatment. Dr. Coburn’s research group has done a lot of work reviewing the lymphadenectomy techniques used in different places, as well as the pros and cons of each approach. Find out more about these studies HERE.

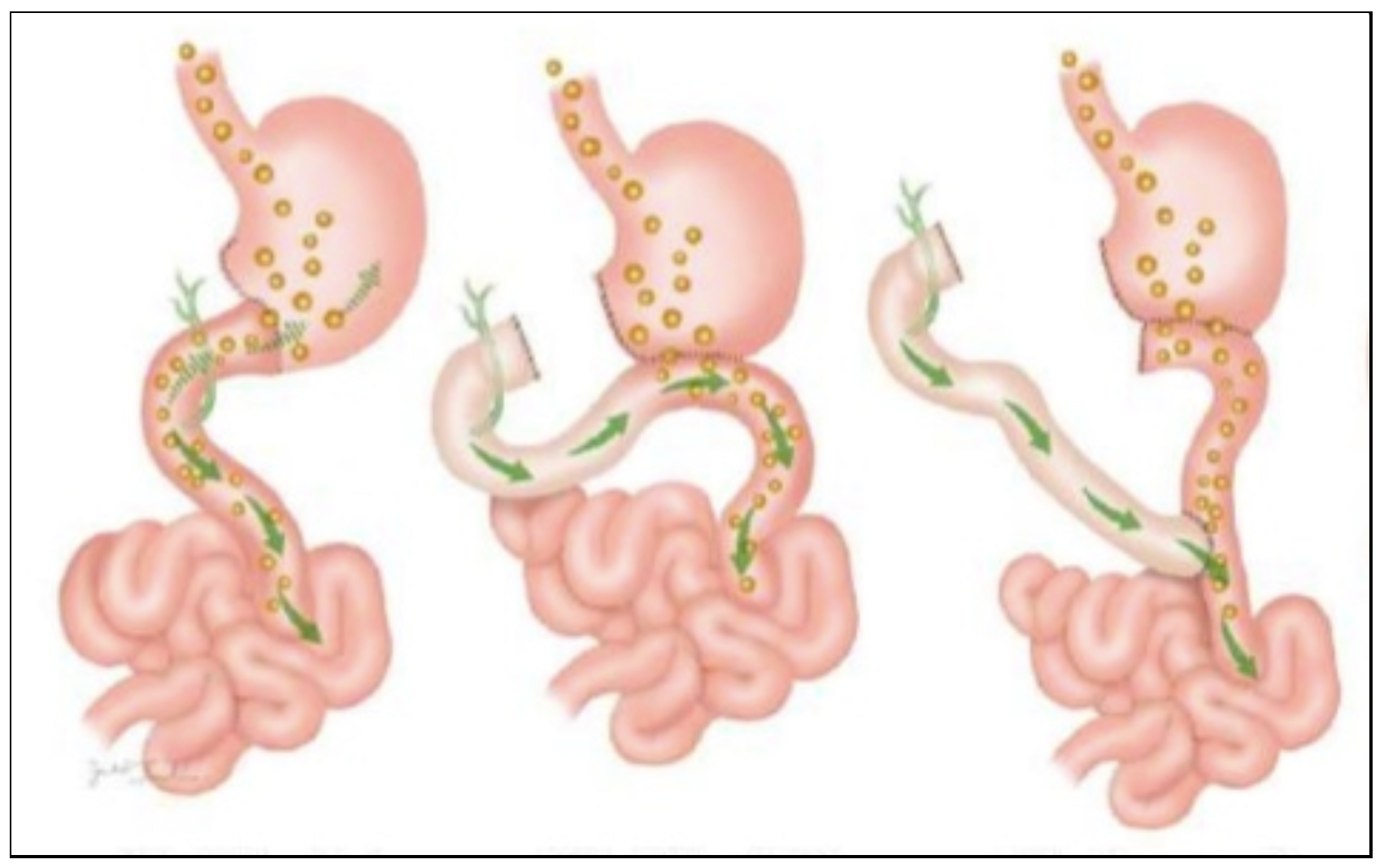

Understandably, it may become difficult to eat and maintain a healthy lifestyle after having part (or all) of a major digestive organ removed. If the GI tract is one long tube from the mouth onwards, how can food pass from one side to the other if the stomach is gone? To avoid this problem, the two ends of the GI tract on either side of the cut-out portion must be reattached. There are different techniques that a surgeon can use to achieve this and ensure the continuity of the GI tract. Three of these techniques are explained here3:

All three of these methods work by sealing together the two cut ends of the GI tract, so that food can pass through uninterrupted from the esophagus to the stomach and the small intestine.

Figure 4: Shows three major reattachment techniques of the stomach to the small intestine after a distal gastrectomy. Far left is Billroth I, middle is Billroth II, far right is Roux-en-Y